InTrans / Jun 06, 2018

New ISU study predicts roosting habitats of threatened bats under bridges

Researchers inspect one of more than 500 bridges as part of this project

Engineers and scientists rarely get together to talk about bats, but when they do, they have unprecedented research to share.

Researchers from the Institute for Transportation (InTrans) at Iowa State University have completed a unique research study that sheds some light on how bats use bridges throughout the state as roosting locations.

Bats may turn to man-made structures for roosting; however, their presence on bridges can complicate construction and maintenance. The need to better understand and predict bats’ roosting habits—to more proactively plan bridge work in the future—was brought up by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Federal Highway Administration, and the Iowa Department of Transportation (Iowa DOT).

Iowa DOT Environmental Specialist Senior Mary Kay Solberg said parts of the study to detect bats on bridges have already been used.

“It was actually incredibly helpful to have that information,” she said. “It worked out really well. Even if someone thinks it’s a bat and it may not be, it’s better to go check it out and look at that possibility than to not.”

Once the Indiana Bat and the Northern Long-Eared Bat were added to the list of threatened species, there was a policy shift among transportation and environmental officials to understand and minimize the impact to bats before working on bridge projects.

“A major goal of the study was to better understand when bridge replacement, repair, and rehabilitation projects have the potential to disturb bat roosting locations in Iowa,” Basak Bektas said.

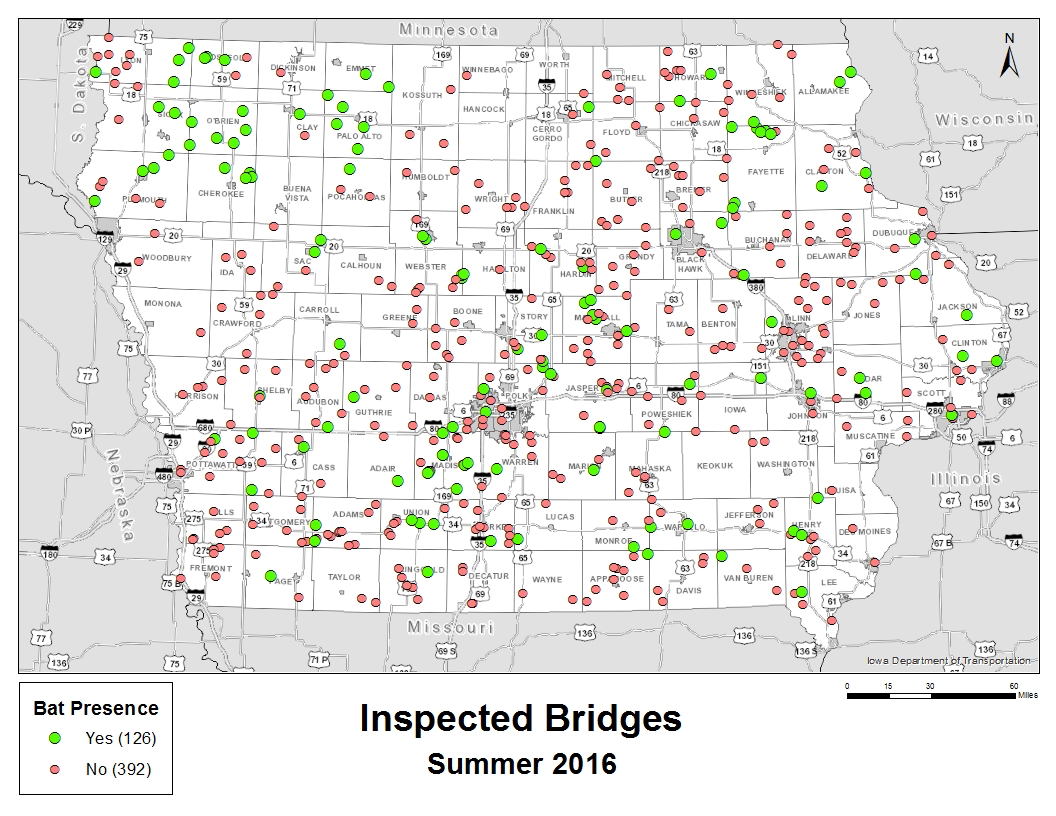

Bektas and her fellow InTrans researchers, including Brent Phares and Zachary Hans, looked at bridge materials, bridge geometrics, and the surrounding ecosystem to determine which elements of a structure are most likely to attract bats. Researchers observed over 500 structures in the state of Iowa and over 100 them had bats.

The data suggest bats are more likely to choose a bridge as a roosting location if it is made from prestressed concrete, perhaps because the concrete retains heat and keeps bats warm. They also found bats prefer structures that are higher above ground, or have more depth within the structure for roosting. Bats are also more likely to roost in a bridge near wetlands, where they can find food.

“We found that some structural characteristics are more important than others. This information gives agencies a chance to look at their networks and be proactive rather than reactive in their decision making,” Bektas said about the way data may be used by agencies going forward.

Solberg sees the potential for a smartphone app that could be used in Iowa, and even nationwide. An app could act as a valuable tool where Iowa DOT and other agency employees could input bridge variables, like those in the study, and get a number that would tell them the likelihood of bats roosting on that bridge.

“Hopefully with this information InTrans has, we can get on top of something like that early enough that we can adjust the project schedule if we need,” Solberg said, adding that, for example, they might demolish a bridge in the winter when bats are less likely to be there.

The research could also provide insight to conservation efforts that, in the past, have otherwise been hindered by a lack of information. Such efforts are driven by a growing concern for bat populations across the country because of white-nose syndrome, which has killed more than 5.7 million bats in North America since 2006, according to the study. Bektas said it could also provide a framework for other states to conduct similar research.

Although there could be many reasons that bats are choosing these structures to roost in, there’s a reciprocal responsibility between ecologists and engineers to understand that bat habitats have been disturbed in the recent past and bats, in response, have found man-made alternatives to their original habitats.

“We’re hoping this research provides a perspective from the transportation side to the ecological side for any potential solutions,” Bektas said.

Article written by Hannah Postlethwait, Institute for Transportation student staff, in collaboration with Basak Bektas.

Contacts:

Basak Bektas, InTrans research scientist, basak@iastate.edu

Christinia Crippes, InTrans communications, ccrippes@iastate.edu